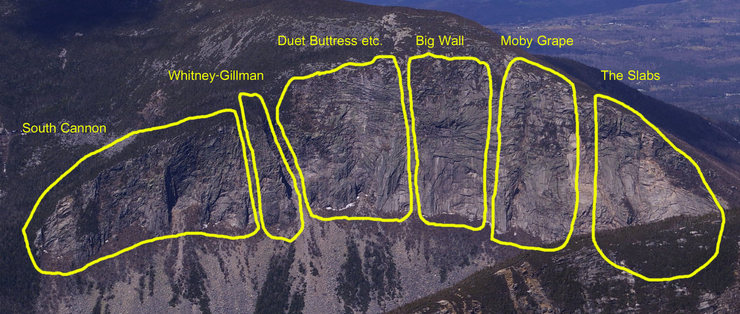

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

Several hundred feet above the ground, I tip-toed across the smooth granite of Cannon Cliff, wedged my fingers into a narrow vertical crack, and inched up toward a triangular overhang that is considered the crux of Moby Grape, a climbing route near where New Hampshire’s Old Man of the Mountain once perched. The rumble of cars driving on I-93 far below through Franconia Notch echoed up the cliff, which was growing increasingly hot as the sun pushed the temperature into the high 80s.

I crouched below the overhang and placed a #2 camelot into a crack above my head, then clipped it to a rope that extended backward more than 100 feet to where Jeff, my climbing partner, was belaying me. Since I could not see above the overhang, I blindly extended my right arm over the roof to where the crack continued upward. My fingers gripped the crack edge. I lifted my left leg upward and smeared my toes against the lower edge of the crack, then slid my right hand upward, wedged it fully inside the crack, and pulled my torso up. My chest was now above the overhang, while my right leg dangled down over the abyss. I inched my hands upward, but I was reluctant to move further until I placed another piece of protection to prevent myself from whipping backward in case I slipped.

I grabbed a .75 camelot from a ring of my harness and stuck it into the crack, where to my joy it stuck snuggly. I then reached down to grab the rope and clip it into the camelot. But the rope wouldn’t budge — it was now dragging over so much rock and through so many carabiners that there was more than 40 lbs of drag weight. I couldn’t pull it. The rope, which had been my lifeline, had suddenly become my chain, preventing me from completing the hardest sequence on the entire 900-foot-plus route. I was stuck. I was pouring sweat. My hands were slipping.

“Get it, Kurczy!” Jeff yelled.

It was Sunday. Jeff and I had driven up from New York City on Friday and camped a mile south at Lafayette Place Campground, where we snagged one of the last two remaining sites. Over the past year, he and I had together learned “trad” climbing (a style that eschews using any types of bolts or fixed gear) and climbed outdoors many times together at the Gunks in New York, but this was our first time at Cannon Cliff, which is one of the biggest climbing walls on the East Coast and a premier climbing area in New England.

Nearing 1,000 feet tall, Moby Grape (rated 5.8) is compared to notable Western U.S. climbs like Yosemite’s Nutcracker or Guide’s Wall in the Tetons (not that I’ve climbed them, but sounds impressive right?). Before doing Moby Grape, we decided to first test ourselves by climbing the Whitney-Gilman Ridge (5.7), which is the only route more popular on Cannon Cliff. After arriving to the campground Friday night, we assembled our climbing gear:

Photos by Jenna Cho

Photos by Jenna Cho

To beat the weekend crowd, we woke at 5 a.m. Saturday and drank instant coffee by a morning fire. We were joined by my girlfriend, Jenna Cho (i.e. The Daily Cho, i.e. The Nacho), who consented to waking early and driving us to a parking lot at the base of Cannon. Looking up toward the Whitney-Gilman Ridge, we could see the headlamps of two climbers already hiking toward the cliff.

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

By dawn, Jeff and I were scrambling up the boulder field, making it to the base of the 500-foot-high, knife-edge Whitney-Gilman Ridge before 7 a.m. It was first ascended in August 1929 by the Yale boys and cousins Bradley Gilman and Hassler Whitney, the latter a mathematical genius who was the grandson of the first surveyor of Mt. Whitney (tallest peak in the continental U.S.).

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

For years, the ridge was considered the hardest climb in America — in good part because climbing gear was so much more rudimentary in those days, with clunky work boots, heavy hemp ropes, no harnesses, and the only protection being metal pitons that had to be hammered into the rock.

Whitney-Gilman’s first pitch was a 5.6ish vertical crack that Jeff led. The second pitch started with a 5.7ish corner and crack that I led. Here I am at the second belay station:

Jeff led the third pitch, a 5.8ish hand crack that progressed up to a vertical corner of the ridge and past a famous metal pipe that was pounded into the rock in 1930 during the route’s second ascent. Jeff seemed especially prone to dropping things during this pitch…

About 10 feet above my head, he dropped a $75 camelot — miraculously, I reached out and caught the device mid-air. Later while I was climbing up to him, I heard something fall down the cliff — I assumed it was a stone, as Cannon is notorious for loose rocks, rock slides, and exfoliating cliffs (most famously the Old Man of the Mountain, which crumbled in 2003). When I reached Jeff, he said to me, “I got some good shots before my camera fell.” The video camera that had been strapped to his helmet slipped loose when he was looking down. “Want to go look for it?” I asked. He shrugged and seemed resigned to having lost the camera. Then on a whim, he yelled down to a climber following behind us and asked if he’d seen a camera fall. The guy yelled back, “You mean this camera here?” It had fallen right next to where he stood.

Here’s Jeff starting the third pitch and then belaying me from the top of it, with the Black Dyke abyss between his feet:

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

The fourth pitch was my turn to nearly lose a piece of equipment. While placing a wired nut in the rocks for protection, I absent-mindedly left a second nut on the ledge. When Jeff later followed my path, he found the $20 piece of gear still balanced precariously on the ledge. Later on another climb, I dropped a wired nut but somehow managed to pin the thing against the cliff with my mouth and hold it there long enough to free up one of my hands and grab it. Incredibly, despite dropping so much gear, we managed to not lose anything we dropped.

The fourth and fifth pitches of the Whitney-Gilman Ridge continued to have thrilling vertical moves and exposed stances over the edge of the cliff, mixed with interesting cracks and fun alcoves, all leading up to a beautiful table-like ledge that looked across Franconia Notch to the 5,000-foot-high peaks of Mt. Lafayette and Mt. Lincoln.

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

Looking across the notch, I strained my eyes to see the hikers high up on the Franconia Ridge between Mt. Lafayette and Mt. Lincoln. Jenna was also up there somewhere, straining as well to try to see me and Jeff and other climbers. She snapped this photo of Cannon Cliff as seen from the top of Little Haystack Mountain:

Photo by Jenna Cho

Photo by Jenna Cho

Since we completed the five-pitch Whitney-Gilman before noon, we naively decided to try to use the remaining daylight for another climb. We hiked down the wooded trail to the base of Cannon, then scrambled back up the boulder field toward the Big Wall area.

By now the temperature was in the high-80s and the full sun was beating down. Sweat was dripping from our faces and soaking our shirts when we reached the base of Moby Grape, which was first ascended in July 1972 by the New Hampshire teenagers Joe Cote and Roger Martin.

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige

Given the relative ease with which we had ascended the Whitney-Gilman that morning, I thought we might be able to quickly do Moby Grape, even if it was a full grade harder and several hundred feet longer up the tallest section of Cannon Cliff. The first pitch quickly proved us wrong.

Neither Jeff nor I had true experience with crack climbing, which might be compared to driving a standard versus an automatic transmission. You’re driving a car either way, but if you’ve never driven stick then you’re likely going to stall out. We both stalled on the 100-foot-long Reppy’s Crack, said to be the “finest” crack climb in the White Mountains. I thought it was murder.

Jeff struggled midway up, then turned back because of the unbearable pain in his feet and ankles from being wedged in the crack. “Most of the time your feet are torqued at odd angles in the crack,” as is warned in the guidebook Selected Climbs in the Northeast, “and if you dawdle you pay for it with painful ankles.” I then took a crack at the crack. I soon noticed smears of red all along the edges of the crack — it was blood from previous climbers, and soon my hands were also oozing on the rock.

After an hour (and many rest points, including a break to remove my shoes and rub my aching feet), I arrived to the top. By then we knew it’d be foolish to try any more of Moby Grape. We were exhausted from hiking and climbing in the full sun; we were also dehydrated and out of water. “If the first pitch is this hard, how can we possibly climb all nine pitches of Moby Grape?” I wondered aloud. The best we could do was keep practicing Reppy’s Crack, with the hope that we might be able to return rested the next morning and climb all of Moby Grape.

A steady trickle of climbers was now passing us as they hiked out. First came the two Navy boys whose headlamps we’d seen early that morning. Then two Connecticut climbers who’d been stranded on Cannon that afternoon when their rope became stuck in a crack; they had to cut the rope free, forcing them to sacrifice untold pieces of gear so they could create numerous rappel stations while lowering down on a shortened rope — they lost hundreds of dollars of equipment. Then came two Vermont climbers who’d turned back after getting lost on the appropriately named Labyrinth Wall.

Exhausted, we also started hiking down the boulder field, closely behind the Vermont boys. We struck up a conversation and started asking them about Moby Grape whether the whole route was as challenging as Reppy’s Crack. They assured us that the opening crack was the hardest sustained climbing of the entire route, especially if we’d never climbed cracks before. They were mostly right.

The next morning, we again woke at 5 a.m. and hiked two miles back to the base of Cannon Cliff, arriving just after those same two Navy boys had again returned in the pre-dawn to Moby Grape. Soon there was a line of eight climbers behind us, all waiting to do Reppy’s Crack.

With fresh arms and familiarity with the crack, Jeff and I fairly quickly climbed the first pitch. To save time, I combined the next two pitches into one long lead, meaning that I was climbing continuously for nearly 200 feet. It was a fateful decision that soon left me stuck on the crux move, unable to continue because of what felt like 40-plus lbs of rope drag…

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige of the Big Wall section of Cannon, including the route Moby Grape.

Photo by Jeffrey Gereige of the Big Wall section of Cannon, including the route Moby Grape.

Desperate to prevent from falling, I shoved my right hand deeper into the crack and turned it sideways, wedging it inside — the rock rubbed my skin raw and caused blood to bead up, but my hand stayed jammed in the crack. Now with my free left hand, I heaved up on the rope with all my strength, collecting just enough slack to bite the rope with my teeth; again I pulled up on the rope, and again I chomped on the rope, creating enough slack between where the rope was in my mouth and where it was tied to my waist that I could clip the loop to the camelot. I seem to recall yelling a lot as I did this — it was all very dramatic.

Now secured above the roof, I inched my left foot upward, then my right, then my hands, until I was balanced on my feet on an inch-wide groove on the wall. I laid my head against the granite and breathed deeply. There were still thrilling moves to come — mantling the giant shark fin-like Fickle Finger of Fate, stemming up a tall pillar that forced me to swing outward over the abyss, and gently smearing up several run-out sections of slab — but nothing compared to that crux. The route finished with a series of vertical, blocky moves that ended on a patio-like rock ledge overlooking Franconia Notch. Neither of us had any battery life remaining on our cameras, but the book Selected Climbs in the Northeast describes the finale of Moby Grape this way: “As you stand on the big ledge above, surrounded by white granite and with peaks soaring above timberline to the east, it is not hard to imagine you are in Wyoming — and hey, think of the airfare you saved.”

Getting down from Cannon Cliff proved another challenge in itself requiring bushwhacking, trail-finding, and steep hiking for about two miles down to the parking lot, where Jenna was waiting for us on the shaded porch of the Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway (oldest passenger tram in North America). She’d last seen us when we left camp at 5:30 a.m., about 11 hours earlier. Jeff and I were covered in pine needles, caked with sweat, with sun-burned lips and cheeks, and, in my case, bloodied hands and legs.

“How was Moby Dick?” Jenna asked.

“You mean Moby’s Crack?” I said.

“You mean Moby Grape?” Jeff corrected.

We jumped into the nearby Profile Lake and washed off the blood, sweat, dirt and pine needles, then drove seven hours back to New York City. It was after 1 a.m when I was finally showered and in bed, lips chapped, hands swollen, and scabs slowly crusting over where the Old Man of the Mountain roughed me up.

Pingback: The Armadillo | Stephen Kurczy

Pingback: Yosemite: Part I | Stephen Kurczy