You could have a world-class modern art museum. Or you could have an amazing art museum spread over a huge outdoor maze of gardens and flowers from around the world, in which case you’d have The Centro de Arte Contemporânea Inhotim.

You could have an excellent cachaçeria. Or you could have an award-winning cachaçeria surrounded by hundreds of rare birds and scary reptiles and weird mammals, which would give you Vale Verde Alambique e Parque Ecológico (where I visited for a June 22 article in Fusion.)

Inhotim and Vale Verde are both very Brazilian, in the way that Brazil mashes together a lot of ideas and flavors and churns out something a bit messy but still oddly pleasing. Brazilian culture is a mishmash. It’s an interracial potpourri of European and African people, foods, and music. Maybe it’s strange to mix a petting-zoo with alcohol, or to hide art exhibits in a jungle-garden maze. But why not?

Both are located outside the city of Belo Horizonte, in southeastern Brazil, where I’m living a few months. Both were also built by rich guys. (Inhotim’s founder is a mining magnate. Vale Verde’s founder is a former Coca-Cola executive.)

I first visited Inhotim, a 90-minute bus trip outside Belo Horizonte. I was dropped in a parking lot, no art museum or other building in sight. A cobblestone path led into the jungle to a ticket booth, where I got a map of the trails that wound through the 5,000-acre botanical garden to various pavilions and buildings with contemporary works by artists worldwide. For an extra fee you could hop on a golf cart zipping between exhibits, though of course I didn’t want to pay and I thought I could use the extra exercise.

One exhibit, perched on a little lookout area with a clear view of the surrounding mountains, was called “Viewing Machine,” by Danish artist Olafur Eliasson. It’s basically a giant kaleidoscope.

Another simple but clever exhibit was American Doug Aitken’s exhibit “Sonic Pavilion” (not pictured), which let me hear the groans of earth emanating from a 633-foot hole in the ground with a mic at the bottom. When a freight train passed miles away, a deep moan echoed through the pavilion.

My favorite exhibit was Brazilian Valeska Soares’ “Folly,” set inside an octagonal room of mirrors. A repeating film of solo dancers projected onto one wall and reflected into infinity on the mirrored-walls around me, making it seem as if I was standing in the middle of the dance floor. Dusty Springfield’s version of “The Look of Love” played. I felt invited to dance.

And then you have the gardens all around and in between everything. One outdoor patio alone was filled with 350 types of orchids, almost all of them flowering for me.

The New York Times wrote in its 2012 profile of owner Bernardo Paz:

A whiff of megalomania seems to emanate from Inhotim’s eucalyptus forests, where Mr. Paz has perched more than 500 works by foreign and Brazilian artists. His botanical garden contains more than 1,400 species of palm trees. He glows when speaking of Inhotim’s rare and otherworldly plants, like the titun arum from Sumatra, called the “corpse flower” because of its hideous stench.

Paz’s philosophy seems to be: Why not?

My legs were sore from running around the maze, trying to see everything in one day.

A few weekends later, after my blisters healed, I took a trip to Vale Verde Alambique, about an hour outside Belo Horizonte. An alambique is a place that makes cachaça, which is fresh-pressed surgarcane juice distilled and fermented (as opposed to rum, which is distilled molasses, the boiled-down version of sugarcane).

I saw Vale Verde’s huge cane-pressing machines and distillation tanks. I saw the storage area where the cachaça ages in oak barrels, some formerly used for whiskey — giving the cachaça a more smokey flavor.

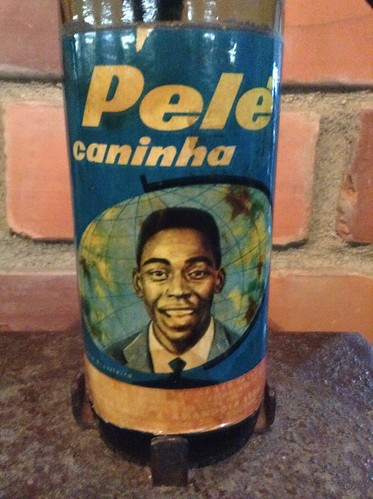

I saw the world’s largest cachaça collection, which includes an unopened bottle of 1958 “Pelé Caninha” produced in honor of the soccer star winning the World Cup. (Pelé had not given permission to use his image, so he sued the company and all bottles were recalled; this is one of only five known to exist. It’s worth about $5,000, according to the guide.)

But I was most amazed by everything that owner Luís Otávio Gonçalves added around the cachaçeria: fishing ponds, zip-line rides, grazing areas for huge ostrich and peacocks and cages filled with thousands of rare birds, including a Blue Macaw (the bird Blu from the movie “Rio”). Gonçalves seems driven by the same “why not?” philosophy as Paz.

And it’s all interactive. Want to feed the Loris birds? Hold a giant lizard? Wrap an albino Burmese python around your neck? (FYI the Burmese python is considered threatened in its natural habitat, but it’s classified as an invasive species in Florida because so many snake-owners have decided that they no longer want to care for a 12-foot-long rat-eating constrictor.)

I thought: Why not?