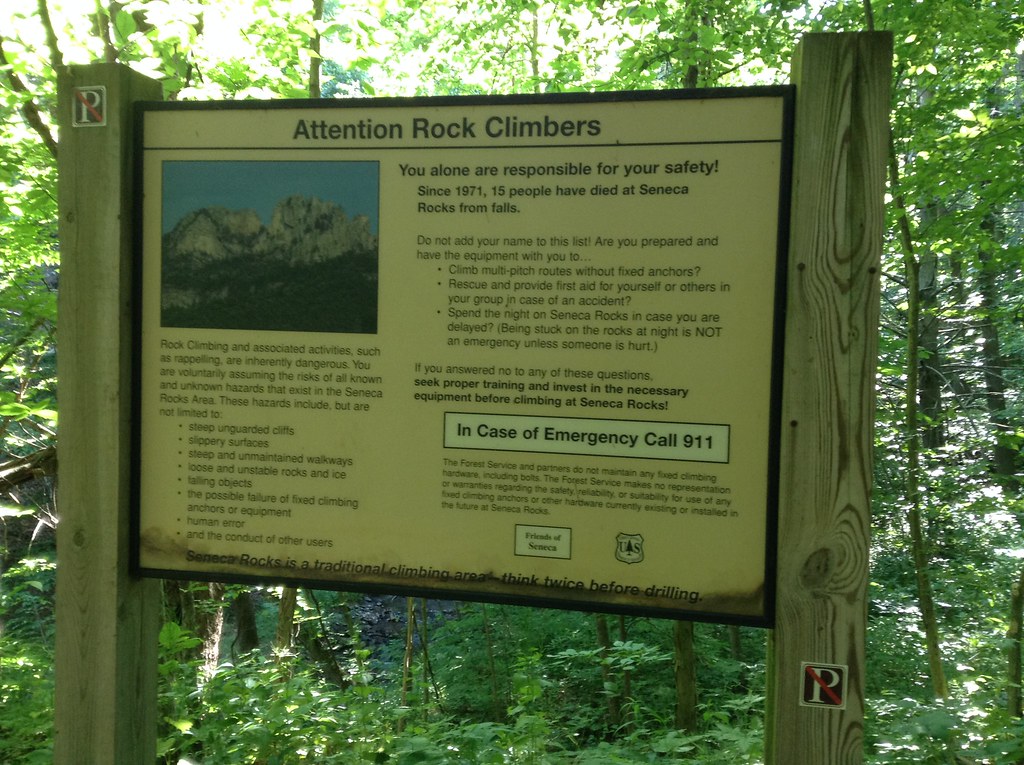

At the spectacular cliffs of Seneca Rocks in West Virginia, a large sign warns rock climbers to call 911 in case of emergency. Thing is, there’s no cell service. Seneca sits deep within America’s National Radio Quiet Zone, where cell service is restricted because of some big and fancy government-owned radio telescopes nearby.

The cellphone dead zone adds to the remote, alpine feel at Seneca, which is one of the taller multi-pitch cliffs on the East Coast and one of the few that requires technical climbing to summit. There’s no way to hike up the South Peak, elevation 2,200 feet (though a hiking trail does reach the North Peak, which is about 200 feet taller). Once you start climbing, there’s no way to hike off and there’s no way to call for help.

Adding to the intimidation-factor, the rock can be chossy and the 300-foot-tall blade that forms the central climbing of Seneca Rocks feels like it might topple any minute. (In 1987, a pinnacle of rock called The Gendarme between the North and South peaks suddenly toppled over, a day after a climber had been on it.) A new months before my first time climbing a Seneca, a climber had warned me, “That whole formation will crumble some day.”

And now here I was, halfway up a route called Gephardt-Dufty (5.7) on the Southern Pillar, scared out of my mind as I rested on a hanging belay, refusing to take the lead.

“I thought we were going to switch off,” said Peat, a climber whom I had just met.

“I didn’t think the climbing would be like this,” I said, terrified the wall could crumble to pieces on us.

Located in the Allegheny Mountains of the Appalachian Mountain Range, Seneca is exclusively trad climbing. One of the oldest climbing areas in the East, Seneca was a training ground for West Virginia’s 10th Mountain Division trained here before deployment to Italy in World War II. Because of the old-school nature of the place, the climbing grades tend to be stiffer than more popular areas. There’s also a fear factor from the high exposure. Because the cliff rises nearly 1,000 feet above the valley floor, you very quickly feel the exposure under your feet.

The approach to Gephardt-Dufty was about one mile up a dirt road and then a steep trail. We were followed by a group of three climbers. Their leader, a local guide, saw us putting on our harnesses at the base of Ecstasy and offered a word of advice.

“Be extra careful with the rock on this route,” she said. “A friend lost his leg on it when a rock fell on him. His leg had to be amputated. I don’t mean to scare you, I just think I’d feel guilty if I didn’t say anything.”

Peat later told me his uncle had also lost a leg in climbing, but it hadn’t slowed him down; his one-legged uncle still climbed and skied. This seemed to reassure Peat that a lost leg wasn’t such a big deal.

Here’s Peat leading the third pitch of Gephardt-Dufty, a five-pitch, 320-foot-long route up the buttress of the Southern Pillar.

Here I am following on the second and third pitches of Gephardt-Dufty (photos by Peat):

Despite my failure to take the sharp end that day, Peat agreed to climb with me again the following weekend. Here’s Peat starting the first pitch of Gunsight to South Peak (5.3), and me following:

I led the second pitch of Gunsight, a short climb up to a traverse across the narrow summit ridge. Freaked out by the 300-foot-drop on both sides of my feat, I crawled across the ridge while more-confident climbers strolled by me without a second thought to the exposure.

Gunsight was relatively short, with two pitches totaling 150 feet, allowing us time for another climb that day: Thais (5.6), a four-pitch, 300-foot route up the South Peak. I led the first pitch, then Peat tackled the second pitch’s chimney.

While I was belaying Peat, another climber high above shouted at me. “Belayer in blue, are you wearing a helmet?”

“No,” I responded.

She shot back: “You should have a helmet! This rock is very dangerous and loose!!”

I nodded, annoyed. What did she want me to do? Tell Peat to hang on while I ran into town to retrieve a helmet?

Soon Peat yelled down, “Take!” I took out the rope’s slack. Peat relaxed on a camalot. “I’m boxed,” he said. “My arms are done.”

After a few minutes, Peat started back up. He veered rightward into no-man’s-land. I cursed to myself, Where is he going? A half-hour later, the rope started being pulled upward. Peat was far out of earshot, so we couldn’t communicate, but I assumed he was secure and it was my turn to follow, though this was just a guess.

I followed up the chimney, then into a slightly overhanging area, and rightward onto a totally different route.

At the summit, we spotted a metal box wedged in the rocks. Peat had said he wanted to sign the “summit log,” but I was skeptical that such existed because I had never before encountered one in all my hiking and climbing around New England. Yet there it was: an old tin box with a clasping latch that somebody had hauled up the mountain decades ago and stashed at the summit.

Peat opened the box. Inside was a bag of weed, a roll of toilet paper, a pen, and a white notebook where we could add our names to the history book for Seneca Rocks.

Seneca is only 300 feet tall. It sits on a 600 foot tall ridge that is climbed by thousands of children and old folks every year. The summit is 900 feet above the river.

And Seneca will still be standing when our civilization is dust.