“Jenna!” I yelled, my voice echoing off the surrounding ring of 3,000-foot-tall walls soaring up to Katahdin, the tallest peak in Maine at 5,269 feet. No response. I was halfway up what Rock and Ice calls “the most remote alpine climbing arena east of the Rockies,” at least five hours from the nearest dirt road and 25 miles from the nearest town, and I’d lost my girlfriend.

“Jenna!” I yelled again, straining my eyes to look down the gully that she was supposed to be hiking up. We’d separated nearly an hour earlier, when I had taken a sketchy detour during our bushwhack to the base of a climbing route called the Armadillo (5.7).

After a long pause, I heard, faintly, “Steve!” I squinted hard and saw a grey helmet pop up from behind a ledge far below. “Stuck!” she yelled.

“Who’s stuck?” I yelled, as the wind picked up and drowned out our voices. “Jenna?!”

Most photos by Jenna Cho

Most photos by Jenna Cho

For five years I’d wanted to climb Katahdin, ever since reading that Rock and Ice article, “The Beast of the East,” which describes the mountain as: “Likely the most alpine setting in the East, this enormous cirque seems transplanted from the Canadian Rockies. Giant crumbling ridges encase alpine tarns; lichen clings to the rocks; gnarled dwarf pines poke from the deep caves between the carefully balanced boulders.” Climbing magazine says of the Armadillo: “A climb this long reaching a true summit is rare east of the Mississippi.”

Katahdin was also my last big peak in the Northeast to tick off. We’d been delayed because of its remoteness (550 miles from NYC) and because of Baxter State Park’s notoriously strict rules and curmudgeonly rangers who ward away visitors; these are the guys who fined the ultrarunner Scott Jurek $500 for “littering” when he spilled champagne while celebrating a speed record on the 2,160-mile Appalachian Trail, which ends atop Katahdin. Hospitality is not Maine’s specialty.

In an attempt to quell the mountain guardians before arriving, I called ahead and explained to the park’s director — Eben Sypitkowski — that I wanted to be sure I was prepared to climb and was following all the quirky park rules. Eben assured me that we’d have no problems and that rangers were much less hands on than in the past, when they’d reportedly inspected climbers’ gear and turned parties away for seemingly arbitrary reasons.

So we loaded up my car and, fueled by whoopie pies, drove up I-95 to Millinocket and then over dirt roads into Baxter State Park, where we camped at Roaring Brook Campground. I had assumed that the park would have potable water at the visitor center — because that’s kind of the definition of what a visitor center provides — despite Jenna’s claim that she’d read otherwise. She was right.

Baxter, ostensibly out of its mission to keep the park “wild” (i.e. inhospitable), refuses to provide drinking water anywhere within the entire 200,000-acre park. Of course, the park also has roads and campgrounds and ranger buildings and dozens of plaques hailing the greatness of the benevolent Governor Percival Baxter who created the park, but not one simple, hand-powered water pump. We drew water from Roaring Brook and filtered it as the sun was setting.

A ranger walked to our campsite, asked us of our plans, and said that we’d need to check in at Chimney Pond Ranger Station with someone who’d inspect all our climbing gear and give us permission to proceed… the infamous mountain of red tape. I started feeling anxious about what was in store for us. The next morning, we planned to hike 3.3 miles to Chimney Pond with all our climbing gear and camping supplies for three days, then climb the Armadillo, which could take anywhere from 5 to 15 hours, based on online reports.

We awoke at 4:30am to an ominous drizzle. We packed in the rain and were on the Chimney Pond Trail by 5:30am. The rain stopped. After an hour of hiking in the dark, the sun lit up the vibrant fall colors all along the trail.

We arrived to Chimney Pond in just under two hours, being “greeted” at the ranger station by a surly park official named Jen whose first words to us were: “You the climbers? I’m expecting a dozen of you today. For some reason you all think there’s only one day of the week to climb.”

“Actually,” I said after dropping my bag, “we’d planned to climb tomorrow (Monday) or Tuesday but the forecast was worsening for those days, so we opted for today.”

“The weather is unpredictable up here,” Jen replied, apparently by way of insinuating that we shouldn’t have come at all. “We prefer if climbers call ahead.”

“Actually,” I said, “I did call ahead.”

“We never got your message,” she said.

“Well,” I said, with growing frustration, “I spoke to Eben, the director of the entire park. He told me some basic rules and said we’d be fine to climb.”

“You spoke to Eben?” she said. “Well, we still prefer you let us know here.”

“Is there a phone here?” I asked.

“There are no phones in Baxter, this is a wilderness area,” she said with pride but without realizing that she’d undercut her previous statement.

After about an hour of this, including an inspection of our climbing gear once I completed a page-long form detailing all our equipment, Ranger Jen finally said we were good to go, but only after a final sermon about the dangers ahead.

“The approach to the Armadillo is similar to what you’d find at Grand Teton,” she said.

“I’ve never been to Grand Teton,” I said.

She shrugged as if to say, Neither have I but that’s what I’m told. It was obvious that she had never personally climbed anywhere nor made this approach hike to the Armadillo. I was fairly annoyed by her whole attitude, though over the next few days I would begrudgingly come to appreciate what she stood for.

By now the morning mist had burned off, revealing our destination. In the below photo taken from Chimney Pond, the Armadillo is the triangular ridge just left of the summit clouds.

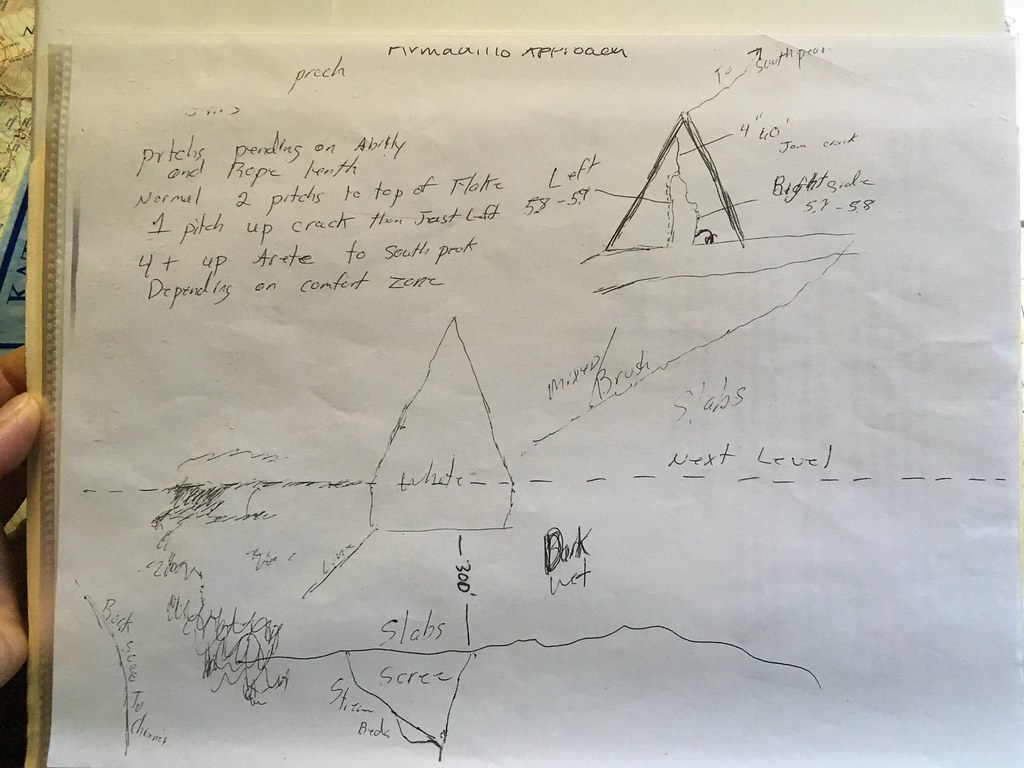

Now that Ranger Jen had thoroughly unnerved us and delayed us for more than an hour, we started bushwhacking away from Chimney Pond at about 9am, just behind two young male climbers. There was no trail. All we had was a general sense of where we needed to end up based on this scribbled map found at the ranger station:

The approach reminded me somewhat of going up Yosemite’s Death Slabs, which lead to the base of the northwest face of Half Dome. But the Death Slabs have fixed ropes through the steepest sections. Katahdin, owing to its “wilderness-first” regulations, bans any form of fixed lines, turning what should be a straight-forward approach into a sometimes-perilous experience.

After about an hour of hiking up a rock-strewn riverbed, we emerged from the woods onto a boulder field. After another 30 minutes of hiking toward the vertical headwall of the south basin, we found ourselves inching up slabs just left of a waterfall (which in winter turns into the Ciley Barber ice-climbing route). Here, we roped up for a 50-foot section with a few exposed 5.6 moves.

At this point, I continued straight upward. As the scrambling turned into technical climbing, I realized that I should earlier have veered rightward into a gully that diagonals rightward toward the Armadillo.

“Don’t follow me!” I called down to Jenna. “Go over to the gully and I’ll meet you further up.”

That was the last I saw of Jenna for the next hour, during which time I felt precariously close to dying as I tip-toed across thin vegetation, grasping onto weeds for protection from falling backward hundreds of feet. At one point, I had to down-climb through a near-vertical gully with my feet dangling underneath me and my hands only hanging onto tree roots. On the upside, however, I found a cool souvenir along the Ciley Barber ice route: an ancient piton, likely freed during the spring thaw six months earlier. Its presence meant that nobody had been where I was in months and highlighted how far off-route I’d detoured.

Finally, I was back inside the gully that Jenna had started up an hour earlier. Above me, the two young men who’d started hiking just before us were now climbing the Armadillo. But there was no sign of Jenna. I called her name, no response. I wondered if she’d given up and returned to Chimney Pond. I called her name again. Several hundred feet below me, I saw her grey helmet poke up from behind a ledge.

After about 15 minutes of down-climbing, I reached Jenna. Barely over 5 feet tall, she faced an 8-foot tall vertical ledge, which was wet with flowing water and slippery from rotting vegetation. I got to the edge of the ledge, securing myself to a camalot that I placed into a crack and then leaning down to help her up. She started to cry.

“I don’t want to be here,” Jenna said.

“I have a pep talk when you’re ready to hear it,” I said. No response. I continued, “We’re almost there. Soon we’ll be roped in and be secure. At this point, it’s easier to go forward than to turn back.”

Some pep talk. Fairly uninspired, Jenna continued with trepidation. After another 30 minutes up the slimy gully, we accessed a narrow, exposed ledge with several sections that required us to swing ourselves outward over a drop-off. It wasn’t hard, but it was a situation where a slip would mean a long fall and broken bones.

And then we were basically at the Armadillo, which starts at the base of a 200-foot-tall detached flake leaning against the mountain. It was 12:30pm. Ranger Jen had given us a turn-back time of 1:30pm, meaning we had one hour to make serious progress. If the approach was this hard, I thought, what else were we in store for?

Pitch 1: The first pitch, a 5.5 chimney, weaved behind the detached flake for about 75 feet. It was pretty straight-forward, though Jenna struggled to get comfortable with all the stemming and wedging (moves that an indoor gym won’t prepare you for). Once she reached me, she started crying again.

“I am not enjoying this,” she said.

“Your nerves are just shot from the scary approach,” I said. “This climbing is well within your ability. I know you can handle it.” I said that while knowing we still faced the crux pitches above us.

Pitch 2: The second pitch was an arete and exposed face-climb graded 5.7, though it felt more like 5.6 — easy protection, good holds, but with big-time exposure beneath our feet. I called back, “When you get here, don’t look down.”

Reaching the top of the flake, I built an anchor by making use of an old piton fastened into the rock. In relatively no time, Jenna sent the pitch — it was two grades harder than the first chimney pitch, but it was more like the Gunks face-climbing that she’d trained on.

“No big deal,” she said when she reached me, smiling for the first time since we’d left Chimney Pond five hours earlier.

Pitch 3: The third pitch, a 100-foot-long splitter crack rated 5.7, is considered the crux. True cracks can be difficult to on-sight if you don’t have crack experience, as I’d found in Yosemite (to my crushing dismay) and also at Cannon Mountain in New Hampshire when first attempting Reppy’s Crack.

The Armadillo crack was nothing but easy fun — painless jams, secure hands and feet, many spots for placing gear. Despite all the dire ranger warnings about the necessity of needing a #4 camalot, I only bothered to place it because I’d carried it all that way. At the top of the crack I reached a wide, comfortable belay ledge. Jenna quickly sent the pitch.

Pitch 4: Directly above the belay was a fun corner (5.6ish) that led up to steep scrambling mixed with 5.2-5.4 moves. I stopped only when I’d run the full length of our 200-foot rope.

Pitches 5 and 6: For each of the final two pitches up the spine of the Armadillo, I again ran out the 200-foot rope. Jenna and I were far out of eyesight or earshot — though we could still hear another party of five climbers on the nearby Flatiron (5.8) yelling and yodeling obnoxiously. I wished that Ranger Jen could have been there to scold them for not respecting the wilderness ethos.

Approaching the summit ridge, the clouds enveloped us.

It was cold and blustery — despite only being the first weekend of October, the wind chill was forecast at 19-degrees F. We didn’t linger any longer than it took us to coil the rope and change our shoes. We walked the summit ridge to Baxter Peak and then descended via the Saddle Trail.

It was nearly 7pm when we returned to Chimney Pond, 10 hours since we’d left and about 14 hours since we’d woken up. We were soon inside our lean-to, preparing a dinner of Korean ramen with tuna by headlamps. At our feet, a pudgy little field mouse scurried around nibbling food crumbs. This was our home for two nights.

Bears have been frequenting Chimney Pond, so there was a strict rule about hanging all food on a bear line in the center of camp.

Exhausted, we slept until nearly 10am Monday. But by 11am we were heading up the Cathedral Trail…

Cathedral was a fun series of steep ledges…

Leading all the way to the summit of Katahdin, which gave us a clear view in every direction onto pristine wilderness, save for a single cell phone tower in the distance…

We found a small crowd at the peak. People were drinking beer and on cell phones. Again, I found myself wishing that Ranger Jen could magically appear to scold everyone for disturbing the quiet, wilderness ambiance.

In fact, there used to be an official rule against using cell phones inside Baxter State Park because of their obnoxious disturbance to everyone all around, and rangers would tell hikers at the summit to turn off their phones unless it was an emergency. “Something as simple as someone pulls out their cellphone on top of Katahdin and makes a call to say, ‘You won’t believe where I’m calling from right now.’ That takes away from someone else’s wilderness experience,” Baxter’s former chief ranger has said. “You don’t want to have to regulate that. But how do you educate not to do that?”

The rule was recently abandoned, I was told by another ranger, because there was too much pushback from visitors.

We continued along the summit ridge’s appropriately named Knife Edge Trail…

Three loud bros who had also just climbed the Armadillo soon passed us. I overheard one of them saying, “If I could return and climb that route cleanly, without any hangs on the rope, that’d be a solid big wall accomplishment.” Little did he know that the small Asian girl nearby had just done what he hoped to some day do.

An older hiker had warned us of “some 5.6 down-climbing” along the Knife Edge. His memory was of much worse than reality, but the “trail” did involve legit scrambling…

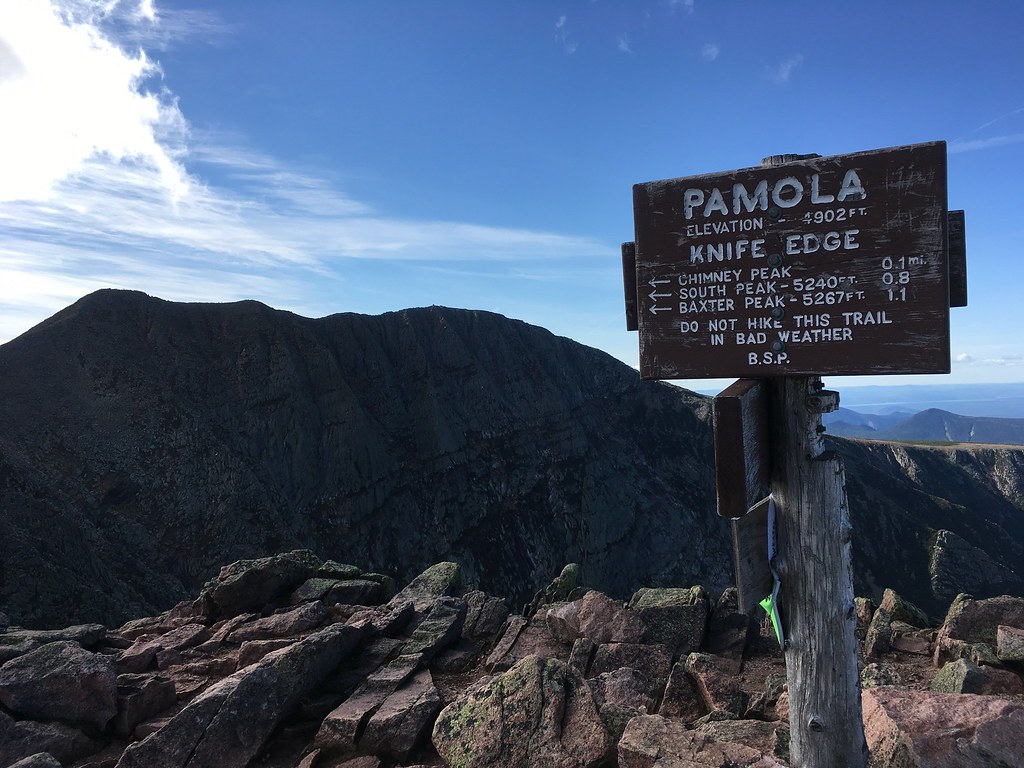

The Knife Edge ends (or starts) at Pamola, a peak named after the legendary bird spirit of Abenaki mythology that protects the mountain (and lent its image to a local beer). With the head of a moose and the wings and feet of an eagle, the god Pamola wields the power of thunder and controls the force of cold air. The Maine explorer Thoreau said of it: “Pomola is always angry with those who climb to the summit of Ktaadn.”

I, too, think we might have angered Pamola. We descended the Helon Taylor Trail and returned to Chimney Pond by dusk, making it a 9.5-mile day. The next morning, we awoke to Pamola’s revenge in the form of the season’s first snowfall on Katahdin. Looking toward the summit from Chimney Pond, we could see a band of fresh white along the socked-in upper ridges.

By late morning the snow had turned to rain at Chimney Pond. Before leaving, we spoke to Ranger Kim, and while informing us about the park’s regulations around cell phones she confessed that a cell signal had recently reached Chimney Pond. It was a little disappointing to hear. It made “the most remote alpine climbing arena east of the Rockies” feel a little less wild and free.

We hiked out amid the drizzle, surrounded by leaves turning red, orange, and yellow.

Then we ate a lot of food.