To climb the 8,839-foot-tall northwest face of Half Dome in Yosemite National Park, you need a lot of gear. Aside from a rope, the leader’s harness is weighted with around 20lbs of quickdraws, alpine draws, wired nuts, and camalots (cams) used to create an artificial safety system as he or she climbs; a potential fall is caught by whatever gear the leader wedges into a crack.

So when Jeff, standing some 700 feet above the ground, dropped our armory of nuts (about eight of them, and essential for completing the remaining 1,500 feet of a route called the Regular Northwest Face, rated 5.9 C1), we felt the wind drop from our sails. Writing this, I can still see Jeff’s nuts falling in slow motion: floating through the air, bouncing off the cliff, and tumbling into the abyss, essentially denuding our ambitions. Then a long silence.

“Sorry man,” Jeff said.

“I have a feeling we’re heading in the same direction,” I said.

It was one of a number of fumbles that led us to bailing and rappelling 710 feet back to the base of the cliff. But I wasn’t willing to let Half Dome slip away so quickly.

Chapter 1: A Predestined Encounter

Jeff and I had dreamt of climbing Yosemite’s iconic half-moon of Half Dome for nearly two years, ever since we first met in New York City.

On the first day of our graduate school orientation, the only two climbers in the entire program (he and I) had coincidentally sat next to each other, two random seats inside a 600-seat auditorium. As we exchanged introductions, I realized that I’d passed through Jeff’s hometown in northern Lebanon a decade earlier when I was backpacking through the Middle East. Then we realized that I’d actually slept in Jeff’s bed; I had stayed with the family of a friend’s friend who, incredibly, turned out to be Jeff’s sister.

Our meeting seemed destined by the climbing gods.

We started climbing together in the city and dreaming of a trip to Yosemite. We watched Valley Uprising. We learned trad at the Gunks and did our first East Coast big wall in September 2017 in New Hampshire. I tested myself in West Virginia at Seneca Rocks and the New River Gorge, while Jeff flew to Nevada and climbed the 1,600-foot-long route Epinephrine — which we read was something of a test for Half Dome. We practiced cracks and aid climbing. We upped our intensity at the Gunks with a marathon 15 pitches in 14 hours.

We set our sights on Half Dome for the first week of June 2018.

We knew Half Dome would be our most challenging climb ever because of 1) the unavoidable aid-climbing requiring ascenders and ladders, 2) the length, at nearly a half-mile of vertical gain, and 3) its meandering nature, which includes several tension traverses and one rope toss (literally tossing one end of the rope about 15 feet sideways into a crack and then pulling yourself across the void). We invested dozens of hours learning about the route, reading about past ascents, and watching videos of people attempting to follow in the footsteps of Royal Robbins, who led the first ascent in 1957 of what was then the hardest rock climb in the US.

Hearing that hauling a bag was one of the worst parts of doing a big wall climb, we opted against bringing a haul bag. Instead, we each wore a small backpack containing all our food, water, and overnight supplies (sleeping bag, puffy jacket, hat, hand warmers). This was potentially a more streamlined way to climb. But without extra food or water, it also removed room for error. It also added 30lbs onto each of our backs.

My three-day food supply totaled 7650 calories and consisted of: three Meal2Go packs (1950 calories), six caffeinated energy gels (600 calories), six protein bars (1500 calories), and one emergency ration food pack (3600 calories).

On June 2, I flew from New York to San Francisco. As my plane soared over the continent, I had an anxiety dream in which I flew to California and Jeff told me that he’d determined he/we couldn’t climb Half Dome after all because it was too hard; in the dream, my initial relief quickly turned to guilt and personal let-down for wimping out. When I woke from the dream, I looked out my cabin window and saw the 8,839-foot-tall peak of Half Dome in the distance, looming over the verdant Yosemite Valley.

Jeff picked me up at the airport and we drove to Merced. After finding a motel, we sorted gear and then studied the topo map at In-N-Out Burger.

Chapter 2: The Approach

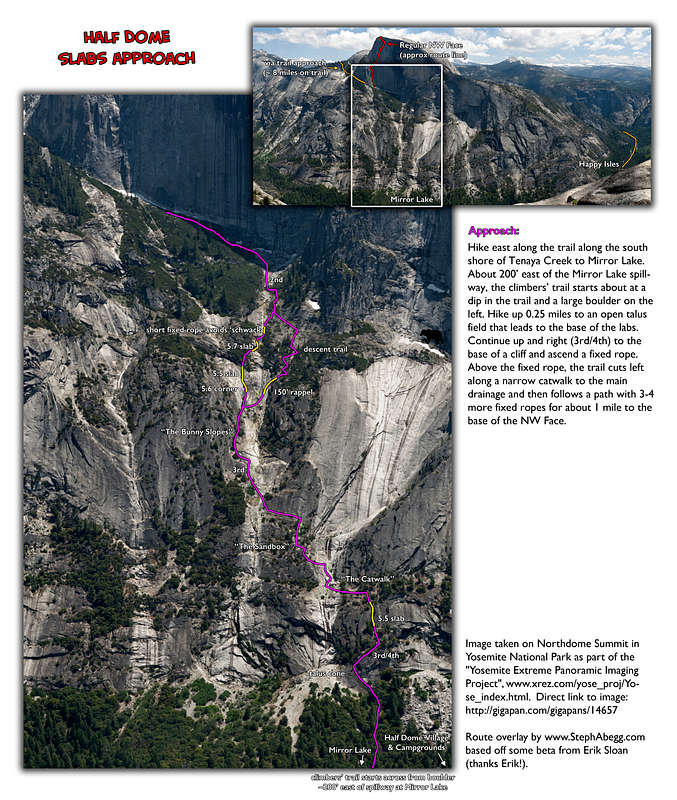

On June 3, we woke at 6am and drove to Yosemite, parking at the Happy Isles trailhead. Along with each of our 30lb backpacks, Jeff carried a 70-meter rope while I carried 20lbs of gear on my harness. Then we began the 2-mile hike toward Mirror Lake, and then the 3-mile hike up the so-called Death Slabs.

Over the next four hours, we hiked, scrambled, and climbed up 3,000 feet.

At two of the steepest sections, we found fixed ropes hanging down several hundred feet. Somewhat blindly, we trusted that these ropes were safely secured, even though, just the night before, I’d read that these ropes had at least once snapped on a climber, sending him tumbling down the rocks.

As a marathon runner, the Death Slabs weren’t so strenuous for me. Jeff felt the heat and elevation gain, stopping often to sit and catch his breath. I don’t think he’d expected the Death Slabs to be so physically challenging, and I’m sure he was wishing that he’d done more aerobic preparation.

“You’ll save your energy if you wait to rest until you’re in the shade,” I yelled back to him.

“Don’t worry,” he said, “I’m going to rest there too.”

We arrived to the base of Half Dome’s northwest face shortly after 2pm. Even though it was around 80 degrees F, a bus-sized stack of snow sat near the start of our route. I found a blue Metolius camalot laying in the slush — no doubt dropped by a climber over the winter and only now revealed by the melt. I added the cam to my harness.

All around us, trunks of sugar pine trees were scarred and gashed from rocks that had fallen from Half Dome, which is infamous for its exfoliation — most notoriously in 2015 when a 5 million pound granite slab crashed to where we now stood. Two fresh water springs were flowing rapidly nearby, allowing us to refill all our water bottles.

Finding a shady site where previous climbers had created a flattish area for sleeping, we unpacked our gear and unrolled our Thermolite sleeping bag liners and bivvy sacks. To save weight, we’d opted against bringing full sleeping bags or sleeping pads. For the next four hours we stared up at Half Dome, tracing an imaginary line along the 2,200-foot-long route that we’d be climbing over the next two days.

Around 6pm, once the sun had eased, we put on our climbing gear and started fixing the first two pitches of the route. By climbing these pitches now and leaving our rope on the rocks overnight, we’d more quickly ascend in the morning using jumars.

Over the next hour, I led the first, 160-foot-long pitch, graded 5.10b and 5.9. I had expected to be able to free climb much of it; instead, I was forced to use my aiders and clumsily aid-climb half the pitch. When Jeff got onto the second pitch, graded 5.8, he also found it too difficult to free. Over this same period, two other climbers — named Greg and Cameron — showed up and free-climbed both pitches in fairly short order.

“How long have you guys been in Yosemite?” Greg said, by way of an introduction.

“We arrived this morning,” I said. “It’s our first time here.”

“Hell of a first climb,” he said dryly. “How did you guys prepare?”

“Are you asking that because we seem unprepared?” I asked.

“No, just curious,” Greg said.

Back on the ground, we sorted gear and ate a simple dinner of pre-packaged foods.

Jeff and I felt apprehensive. On the East Coast, we were free climbing routes graded 5.10 and 5.11. Now at Yosemite, we were struggling with a mere 5.8, and we weren’t yet wearing our 30-pound backpacks. Our entire plan for climbing Half Dome was contingent upon being able to swiftly free climb all pitches rated 5.9 or easier, but that plan was crumbling under reality.

We would need to climb 17 pitches the following day to reach Big Sandy Ledge, our overnight “camp site”; if we started at 5am, that’d give us 15 hours before sunset, which meant we had to climb at a pace of about one pitch every 45 minutes. This meant we should arrive by 10am to the start of Pitch 7, at which point the route veers sideways and retreat becomes more difficult, if not impossible.

With that goal in mind, we agreed to an absolute deadline of arriving to Pitch 7 before 11am. If we couldn’t complete the first fix pitches by then, we’d bail.

As we were crawling into our sleeping bags at 9:30pm, two more climbers showed up. They said they planned to climb the entire route in one push the following day, leaving at 3am. We hoped to be somewhere behind them.